Part One concerns the reception of May the Twelfth up until the 1990s.

Part Two concerns the ideas involved in the formation of MO and why they were interested in the coronation of George VI.

If Charles III was a Shakespeare play, would it be a history or a tragedy? This is the question that Mass Observation implicitly asked of George VI by prefacing the chapter of May the Twelfth describing his coronation procession with this Henry V soliloquy (from Henry V, Act IV, Scene I, l.238-293). If you can replicate the system by which the king maintains the peace ‘whose hours the peasant best advantages’ then it’s all set fair for ‘Cry “God for Harry, England, and Saint George!”’. If you get it wrong, then everything is going to go a bit Macbeth. The following analysis – the third post in my blog series on May the Twelfth – examines how MO unpick the mechanism within the 1937 coronation which legitimised George VI as King (with Humphrey Jennings positioning himself as a twentieth-century Shakespeare; although you have to imagine this bit yourself). The independence of the king resides in the independence of the masses in attendance. However, if you compromise that independence by, for example, asking everybody to swear allegiance during the coronation service, then you risk upsetting the entire process by which the English monarchy functions. Therefore, I don’t think the omens are good for Charles’s kingship. The somewhat desperate, pleading tone of the (muted) coronation preparations is setting the stage for sorry tale of hubris and downfall.

The material here is mainly from my PhD but the 2000 words or so on the coronation scenes from May the Twelfth were a reworked version of what was in my MA dissertation anyway. I’ve supplemented this by reinserting a dissertation paragraph (the one concerning people throwing sweets to the soldiers lining the route; I think I did restore it for the book version but it’s not in the PhD). I’ve invisibly edited what follows slightly more than the previous two posts because I’ve had to cut out most of the detailed references to Empson and Orwell, but you can still see the traces.

* * *

May the Twelfth: Mass-Observation Day Surveys 1937, edited by Humphrey Jennings and Charles Madge,is in five parts; the first four of which are textual montages – one of press clippings and the other three of extracts from observers’ reports – concerning 12 May 1937, the day of the coronation of George VI. This material was primarily selected and presented by Jennings.[1] A fifth section consisting of complete and abridged day-surveys in succession (rather than montage) was edited by Madge. Other helpers with the editorial process, including William Empson, are listed on the title page. The account of the actual day in London including the Coronation itself and its procession fits many of the criteria of Empson’s theory of proletarian pastoral as outlined in Some Versions of Pastoral (1935). Significantly, this section begins with the entire soliloquy from Henry V, Act IV, Scene i. Empson discusses the character of Henry in Some Versions of Pastoral, arguing that ‘there is something fishy about him’. The point is that ‘the Henries are usurpers; however great the virtues of Henry V may be, however rightly the nation may glory in his deeds’, Shakespeare has a ‘double attitude’ to him.[2] The soliloquy demonstrates Henry’s ironic acceptance of the conventions of kingship – thus giving him a level of self-awareness above that of the average yeoman:

O Ceremony, show me but thy worth.

What! is thy soul of adoration?

Art thou aught else but place, degree and form,

Creating awe and fear in other men?

Wherin thou art less happy, being fear’d,

Than they in fearing.[3]

But conversely, he is well aware of the free pleasures of living life beneath the ceiling of conventions and by understanding and acknowledging the importance of the independence of the common people in this respect, he achieves a level of personal independence and mastery that marks him out as the monarch:

And but for ceremony, such a wretch,

Winding up days with toil, and nights with sleep,

Had the fore-hand and vantage of a King.

The slave, a member of the country’s peace,

Enjoys it; but in gross brain little wots;

What watch the King keeps, to maintain the peace;

Whose hours the peasant best advantages.[4]

Henry’s consciousness of this relationship, and his consequent agency, derive from his knowledge of himself as playing a part. Shakespeare’s own double attitude allows him to pose as critic or admirer depending on your viewpoint, safe from the charge of sedition, while at the same time proclaiming his own superior level of conscious agency as the person who writes the narrative.

Following this quotation, the chapter’s description of the scenes in London on coronation day, proceed like the Shakespearean double plot of heroic and pastoral – only with the heroic half missing. We see nothing of the king but only the crowds lining the procession route.

In respect of these crowds, Jennings and Madge were alive to the potential for political misuse of the ‘revival of a wartime atmosphere’ – obviously added to by the presence of large numbers of troops mobilized to line the procession – and the ‘curious record-hunting ascetic feeling’ revealed in the desire of people to queue through the night in order to be part of the proceedings.[5] The text refuses complicity in these processes by means of its technical composition. This is accomplished by intercutting a series of examples of the crowd reducing the threat of the military by their comments and behaviour – ‘There goes the Salvation Army’; ‘Where ’ave they ’oused all these soldiers?’ (footnote in text: ‘In spoken English you would more often talk of “housing” an emu or an elephant; the idea that soldiers are pet animals seems to crop up here.’); ‘feeding the troops’ by throwing sweets at them[6] – with a series of analogies that deflate the idea of taking part in a momentous occasion: ‘Some of these people look as though they were going to a funeral not a Coronation.’; ‘I heard one of my neighbours remark that she thought it was like dog-racing – something to see for a short time and then nothing for considerably longer.’; ‘…the route is lined with soldiers who are standing in front of a mass of people who look like refugees from Guernica.’; ‘One damned thing after another.’[7] But more subversively, by switching the focus entirely to the crowd, the monarchy – supposedly at the centre of attention – disintegrates into a precarious existence of glimpsed coaches and confused identity reflected in snatches of vigorous argument from the street lining crowd:

Woman: ‘No, not yet. I think the Duchess first.’

Another: ‘That’s the Queen.’ Then, disappointed: ‘No.’

‘That’s Queen Mary.’

‘That’s Princess Marina.’

‘Princess Royal, that is.’

‘The Queen of Norway.’

‘I saw Marina.’

‘I’m sure Queen Mary’s next.’

Man shouts: ‘Hullo, George, boy. Well, Marina.’

Woman: ‘This is Queen Mary’s coach next.’

(It is evident that no one in the crowd actually knows who is who.)[8]

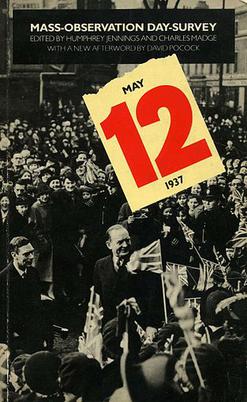

Hundreds of years of existence as the half-erased traces of a history written by the victors is overturned by a ‘camera’ shift. This is illustrated by Jennings’s own photographs taken on coronation day (not included in the book), which show jumbles of heads, legs and feet; against backgrounds of litter, leaves, London Underground arches, steps, scaffolding of stands, trees against the skyline, statues and lampposts.[9] Together, these form an exploration of the possible metamorphoses of public space which pays no attention to the king and stands as a direct challenge to a more conventional ‘news reel’ style depiction of a large flag-waving crowd perfectly foregrounding the important personages at the front – such as the photograph unfortunately chosen for the cover of the fiftieth anniversary reissue of the book in 1987.

This ambiguity – the possibility of either type of representation – is encapsulated in Mass-Observation’s introductory declaration that what is being presented is a ‘panorama of London, and especially of the route of the Coronation procession’.[10] The panorama was originally one of the means by which landscape was brought closer to humanity by technical reproduction. The landscape is ripped out of its function as a material reference point and can either be mythicised as a set of interchangeable units within a totality of exchange or rivally mythicised as liberated public space. Within the modern techniques of conventional mass media representation, the coronation procession, itself the remnant of a mythic hierarchy now secularised to situate humanity in a totality embodied in the symbolic public figure of the king, had the capability of inducing a previously unachievable total participation in the event. One way this was done in practice, despite the actual physical progress of the procession following a scheduled route, was through a system of loud-speakers relaying the cheering of the crowd from the point actually being passed by the procession around the rest of the route and so creating a dislocating shock triggering involuntary participation. This is felt by the observer who reports ‘the most stirring incident was the unreasonably (so it seemed) fervent cheering I felt compelled to give with others to the King and Queen on their return’.[11] It is more strikingly shown in the account of another observer who says of her young daughter: ‘When the show was over I found Lydia (5) still croaking dreary and monotonous cheers until I stopped her.’[12] May the Twelfth fractures this temporally-induced dislocated participation temporally by appealing beyond dislocation to a heightened apperceptive awareness. We do not follow the procession, we follow a chain of observers around the route reporting on overlapping time spans. We do not perceive the disconcerting relayed roar of the crowd as a continuous burst of manifested total being; but as a series of relayed roars, a series of relayed injunctions not to throw streamers out of the windows, a series of repetitions from some other distant plane of existence that seem no more than a faintly ridiculous officiousness when compared with the immediate experience of beer drinking, singing, tree climbing and courting.[13] The technical effects of Surrealist-inspired montage have been used to create a narrative irony overlaying the irony of the coronation double plot.

There are fundamental questions as to what Mass-Observation’s carnivalesque demonstration of this momentary independence of the masses achieves. It could be argued that this independence exists only through the social relationship with the monarch: that the king’s pure consciousness of being-for-self, and hence his authority to rule, is guaranteed precisely by the independence of the masses’s being-for-others, and vice versa. Therefore, May the Twelfth holds the independence of the coronation crowds open at exactly the moment when its public manifestation is required in order to legitimate the new king; and in reality that moment was just converted back into information in the form of radio and television broadcasts and film reels flown round the country to be shown that very evening.[14] Everyday life resumed and the public crisis over the Abdication came to an end. The resistant plenitude identified was not ultimately a threat to the social order: it was the underpinning of that order.

However, such a reading would be blind to the strategies adopted by Jennings, who crucially is both in the text as one of the observers (CM1) and operating at a level removed as the editor. The independence of the masses depicted in the sequence is not a consequence of their social relationship with the king, but a consequence of their textual relationship with Jennings. The technique is analogous to that used by George Orwell in The Road to Wigan Pier, with Jennings using the interplay between his textual and editorial personas, to transfer his artistic independence into a collective independence. To these ends Jennings adopts a similar aesthetic of half-parody to that favoured by Orwell [Ed: e.g., in the account in Wigan Pier of the ideal working-class family in which ‘the children are happy with a pennorth of mint humbugs, and the dog lolls roasting himself on the rag mat’]:

At Hyde Park Corner Rovers are hurriedly putting up a metal barrier in the centre of the street where a lot of cardboard boxes (left by periscope and chocolate sellers) are lying on the ground in the rain. They are now as slippery as banana peels. A girl is lying on the ground in the arms of a policeman.[15]

It is the same mixture of a parody of lost plenitude and the last remaining vestiges of that plenitude, compiled in the same knowledge that the moment described is not going to last: ‘The open stands are empty. The statue of Byron shines in the rain. The police are reforming their units.’[16] These images (and Jennings’s photography) are, to use an analogy from Walter Benjamin, like crime scenes posing a challenge to the viewer.[17] Consequently, rather than the effect David Pocock has ascribed to the book of ‘putting the reader there as though she or he were watching from the top of a slow-moving bus’,[18] we are invited to become detectives but – with ‘no criminal’ to catch – in a case that can never be closed: an unrelenting investigation of everyday life which is ‘at once a rejection of the inauthentic and the alienated, and an unearthing of the human which still lies buried therein’.[19]

By mapping the moments of crisis and resolution, Mass-Observation had fulfilled their original intention of bringing some of the unconscious mechanisms of everyday life to light, which could then be used in analyses beyond the coronation situation. Madge used these to formulate a tentative theory of society, which was crucial to their work in the period during and immediately after compiling May the Twelfth, as confirmed by the following statement from the leaflet, ‘A Thousand Mass-Observers’:

The main study of Mass-Observation at present is in fact the impact of society on the individual. ‘Society’ is an abstract word but it represents concretely to every single person a whole number of other people who affect his life. These people are of three types – they fall into three areas. Nearest home, in what we term Area One, are his (or her) family, the people he sees every day in his home or lodging and at his place of work. Then comes Area 2: meetings with strangers. Outermost, but of peculiar power in influencing his life, is Area 3, filled by all those names of celebrities and public figures, film-stars, footballers, kings, mythical heroes, characters in news, history and fiction; people like Gracie Fields and Earl Baldwin, whom he may only see or hear at secondhand, on the wireless, on the screen, in the newspaper, in books; people who govern him, affect his actions and the way he parts his hair … M-O is studying the shifting relations between the individual and these three areas, thus seeking to give a more concrete meaning to the abstract word, ‘society.’[20]

This concept of the three social areas – illustrated in May the Twelfth with a diagram of three concentric circles[21] – is, as Empson would say, worked from the same philosophical ideas as proletarian pastoral. Area 1 is the everyday part of life not governed by social conventions. Area 2 is the public sphere where conventions do hold sway. Area 3 is the realm of leaders and celebrities, which appears to have been constructed by Mass-Observation through an exploration of the analogy between the relationship between the king and his subjects and that of the modern relationship between the media and the masses:

The King is the archetype of all the personages in area 3. On the great public occasion of his Coronation he exhibits himself in the flesh to his subjects. This is obviously of the greatest importance as a means of establishing his position at the centre of the entire social system. Hence it is that broadcasting plays so vital a role, in enabling the contact between areas 1 and 3 to be effected on a far wider scale than has ever been possible hitherto.[22]

For Mass-Observation, the independence of the king, like the independence of Shakespeare’s Henry V, is the independence of Empson’s third level of ‘comic primness’ [Ed: a term Empson uses in Some Versions of Pastoral]: the ability to accept and revolt against convention at the same time. Monarchy is only one possible expression of this independence and no longer the model for all other relationships in society. However, the very fact of its anachronistic survival allows the media’s role in determining societal relationships to be made visible. The dilution of the dialectical nature of the relationship between the king and the people to just one moment among a chain of differences demonstrates the ability of the media to bridge the gap between areas 1 and 3, thereby eroding the role of area 2. By analysing the contradictions so momentarily visible, Mass-Observation were unearthing changes akin to what Jürgen Habermas later described as the structural transformation of the public sphere.

Therefore, by the summer of 1937, Mass-Observation had built up an organisation, prepared a huge work on their coronation day-surveys due to be published in September and formulated a potentially productive theoretical framework for their further investigations. Through their fundamental commitment to incorporating the subjectivity of their volunteer observers – observation of the masses by the masses for the masses – they were poised to advance beyond merely signifying the possibility of a new class alignment, towards actively promoting it. To this end, Mass-Observation announced in July: ‘Early in 1938 a conference will be held to which all Observers who have worked for over six months will be asked to come. A series of local conferences has already begun.’[23] The Popular Poetry programme of 1936 [see Part Two of this series] was still on course to meet its objectives of helping to realise a new society.

Here is the link for Part Four.

[1] See Madge, Autobiography, p.72.

[2] Empson, Some Versions, p.87.

[3] Jennings and Madge, May the Twelfth, p.87.

[4] Ibid., p.88.

[5] Ibid., pp.91-92.

[6] Ibid., pp.139, 141, 147.

[7] Ibid., pp.117, 121, 122, 140.

[8]Ibid., p.134.

[9] See M-L Jennings, Humphrey Jennings, p.16.

[10] Jennings and Madge, May the Twelfth, p.91.

[11]Ibid., p.138n.

[12]Ibid., p.131.

[13]Ibid., pp. 137-139.

[14] Ibid., pp. 286-287.

[15] Ibid., p.144.

[16] Ibid., p.145.

[17] See Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Illuminations,pp.219-220.

[18] David Pocock, ‘Afterword’ to Jennings and Madge, May the Twelfth (1987 edition), p.419.

[19] Michel Trebitsch, ‘Preface’ to Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, Volume 1, London: Verso, 1991: p.xxiv.

[20] Mass-Observation, ‘A Thousand Mass-Observers’, undated but from internal evidence published in late July or early August 1937, M-O A.

[21] Jennings and Madge, May the Twelfth, p.348.

[22]Ibid.,p.14n.

[23] Mass-Observation, ‘A Thousand Mass-Observers’.